HOUSING

Total housing stock in Afghanistan’s 34 provincial capitals is 962,467 dwelling units. The vast majority of the housing stock is irregular, detached or semi-detached dwellings (524,074 units), followed by regular detached dwellings (315,556 units); and hillside dwellings (71,788). Kabul is the only city where apartments form a significant share of the housing stock with 7.8% of the total dwelling units (including 2% mixed-use apartments with commercial uses on ground floors). Access to adequate housing is a major challenge for the majority of urban Afghans. Poverty and inequality are the harsh reality for roughly one-third of all urban households. This combined with a lack of affordable housing options and an oversupply at the top end of the formal housing market results in a difficult housing situation for low- and even many middle-income Afghans.

Total housing stock in Afghanistan’s 34 provincial capitals is 962,467 dwelling units. The vast majority of the housing stock is irregular, detached or semi-detached dwellings (524,074 units), followed by regular detached dwellings (315,556 units); and hillside dwellings (71,788). Kabul is the only city where apartments form a significant share of the housing stock with 7.8% of the total dwelling units (including 2% mixed-use apartments with commercial uses on ground floors). Access to adequate housing is a major challenge for the majority of urban Afghans. Poverty and inequality are the harsh reality for roughly one-third of all urban households. This combined with a lack of affordable housing options and an oversupply at the top end of the formal housing market results in a difficult housing situation for low- and even many middle-income Afghans.

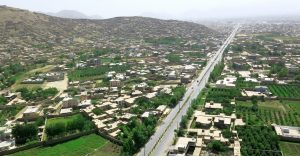

As is the case in many rapidly urbanising developing countries, a large proportion of Afghanistan’s middle and low-income households have come to reside in poorly located and under-serviced informal settlements. In severely contested space, overcrowding is a pervasive issue. Many households accommodate more than one family. The majority (86%) of the urban housing stock in Afghanistan can be classified as a ‘slum’ as per the UN-Habitat definition: lacking one or more or the following basic elements of adequate housing: (i) access to a safe water source, (ii) improved sanitation, (iii) durable, structurally sound housing materials, (iv) adequate living space and (v) security of tenure. The legal and regulatory framework governing land and property registration is inefficient, ambiguous, prone to corruption and inaccessible for significant portions of the urban population.

The process of registering land and obtaining title deeds is both complex and costly. It is estimated that only 10% of land transactions are conducted in accordance with the formal legal procedure.2 The expense involved in land registration is also a significant disincentive to engage with the formal system; with a court fee of 3% of the total land value as well as an additional 2% of the land value for the municipality and Ministry of Finance fees. The procedure to obtain formal approval for a planning and building permit is equally complex, costly and time consuming. The process begins with the submission of an application form to the municipal district/nahia, who then verifies if the proposed land use complies with the zoning denoted under the master plan. There are no publically available copies of the master plan or any scope for the public to complete this process. A simple activity is thus rendered a procedural bottleneck that is susceptible to corruption. Following this, the municipal property department is required to check if the owner has any outstanding safayi tax bills to be paid.

The fact that safayi tax debts are not examined proactively but rather ‘reactively’ in this manner when an application is made is a further disincentive for landowners to deal with the municipality. Engineering departments then verify if a proposal complies with various standards of structural integrity. Meanwhile planning departments are responsible for verifying if a proposed use is in keeping with the ‘orderly and proper’ development of the city (i.e. not incompatible with surrounding land issues), as well as various district and local planning schemes. Each process typically involves a distinct set of bureaucratic steps, all of which are susceptible to corruption. If a permit is issued applicants are obligated to complete building within three years. The municipality meanwhile is obligated to send staff to monitor construction and verify the development’s compliance with approved plans.

Relevant

Local Integration of Vulnerable Excluded & Uprooted People (LIVE-UP)